The Dakar Rally is the most gruelling event of its kind in the world today, spanning 4903 miles of Arabian desert.

Yet its original route covered 6200 miles, linking Paris and the Senegalese capital from which it takes its name. And there have been even longer rallies than that, including one traversing the entire length of Africa, from Algiers to Cape Town.

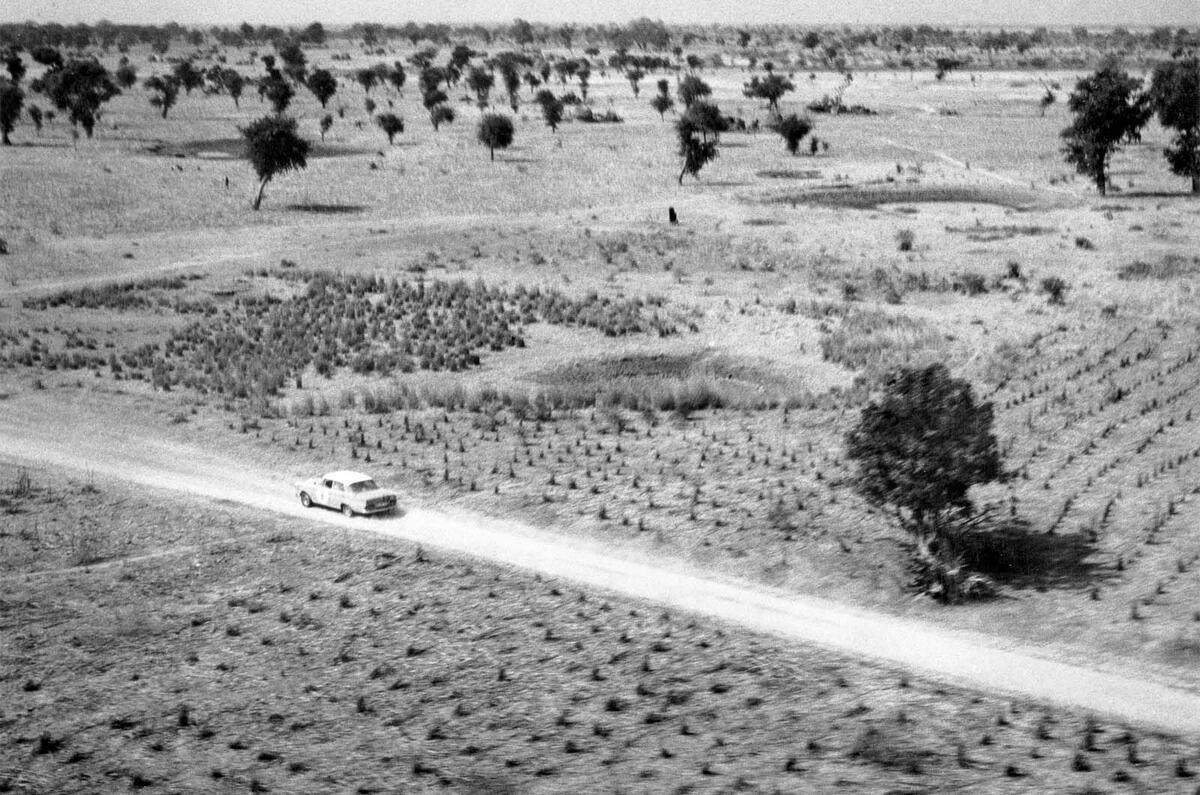

The 1961 edition of said rally was shortened due to political issues in the Congo region, but the distance to Bangui, capital of the then newly founded Central African Republic, was still 7145 miles – and with the Sahara desert, Sahel savanna and vast grasslands being in the way, less than 1% of those were on paved roads.

Long-distance rallying is a French thing. When the French held the world’s first motor races in the 1890s, they weren’t round tracks but point-to-point dashes.

Rallying in Africa began in 1930 to commemorate a century of French rule in Algeria. Organised by the army in collaboration with oil companies, this was a muscle-flexing exercise across France’s West African empire, the rallies being won by Citroëns, Delahayes and Peugeots.

By the time of the 1961 Rallye Algiers, however, Mercedes-Benz was a dominant force in the sport, and the German manufacturer enlisted Peter Rivière – a Brit who had come to attention as an Oxford student as part of an anthropology expedition through South America in a Land Rover – as one of the drivers for its W111-generation 220 SE saloons, alongside Swiss research engineer and single-seater racer Michael May.

“As expected, the cars were prepared perfectly, down to the smallest detail,” reported Rivière in Autocar. Except “the rear and side windows had been replaced by much lighter plastic."

"What hadn’t been realised was that this material has strong static electrical properties, and after the first few miles it was impossible to see out because of the dust clinging to the windows. Rubbing it off only made things worse, since the rubbing increased the electrical charge.”

Apart from that, the trip over the Atlas mountains was uneventful, if not for the heavy traffic that had churned up the road while carrying equipment to the French atomic research base (a year prior, scientists had tested a nuclear bomb at a still-classified location, releasing four times the energy of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima).

Once into the Sahara, another mistake became clear: “The provision of lightweight sand mats, instead of more normal plates or ladders. In practice they proved completely useless.” At one point, “after half an hour’s work digging we had not moved the car a single inch forward but about two inches downward”.

On multiple occasions, the duo had to be helped by “incredibly friendly Saharan lorry drivers”, who not only pulled cars free but also “stayed with us until repairs had been completed and did much of the work themselves”.

It wasn’t all hard graft, mind you: dinners included freshly caught gazelle roasted in desert moonlight in Niger.

Rivière found that “depending on the consistency of the surface, one’s speed varies between 75mph on soft ground to 100mph on firmer”. But he was “very glad to get to the finish”, as problems persisted all the while.

The radiator hose splitting, the spark plugs needing replacing, the differential leaking, a cylinder filling with water and a “plague of punctures” had all caused “May to say a prayer or a swear word in his mother tongue”.

The hole in the floor letting dust in and the need to have the heater on full blast to keep the engine temperature down also made the trial more gruelling.

The #8 entry was overtaken by a Citroën and an Auto Union in the latter stages of the rally, but two other 220 SE crews held on to make it a one-two for Mercedes.

And despite everything, it was an experience that Rivière would look back on fondly. He concluded: “People often say to me how dull it must be, driving across these vast, flat expanses. I do not find it so. There is something wonderful about the scenery on that scale.”